That Rapid Rise and Fall of WeWork: What Comes Next?

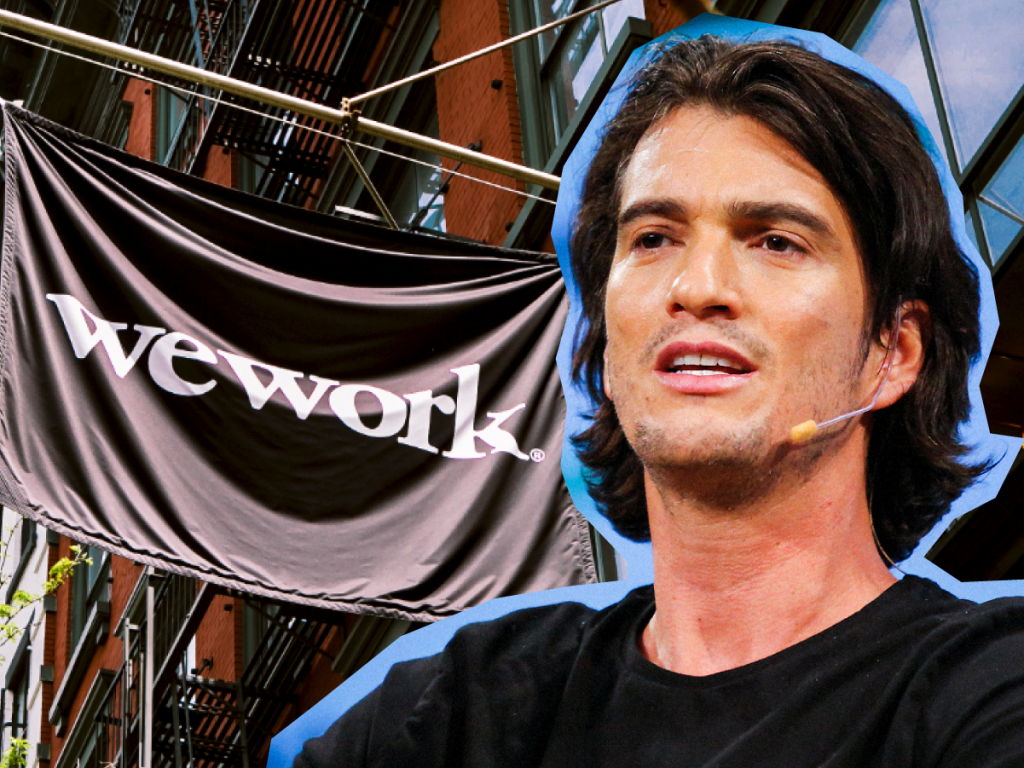

Anyone that has been actively following the news over the last 2 months has been bombarded with stories about WeWork. From founder Adam Neuman’s questionable related company transactions, to the companies worsening financial profile, to the aggressive degradation of its valuation. WeWork seems to have fallen into mediocrity quicker than any of the Silicon Valley darlings before it. The more interesting question to ponder is what does the WeWork fiasco tell us about the VC funding model and the innovation economy of tomorrow?

Without delving into a point-by-point evaluation of the “We” Company’s now infamous community-adjusted EBITDA defense, one simply needs to look at the fundraising and cash burn numbers to realize that this was never a sustainable business model. Raising ever larger amounts of money to purchase growth without a plan or reasonable vision for becoming profitable is not a profile that is palatable for most. However, with some flashy positioning, millennial-inspired perks, and impeccable timing, a real estate company became one of the hottest new companies in the United States. It what seems like a story line out of HBO’s Silicon Valley, venture investors tripped over themselves to throw money at the startup. From August 2017 to early 2019, WeWork raised more than $10bn in fresh capital, all from SoftBank. As the round sizes and valuation numbers grew larger, the money seemed to flow ever more aggressively from the broader Asia-Pacific. In its last publicly disclosed valuation, WeWork raised $2bn at a valuation of $47bn in January of 2019.

With a need for capital that was outstripping the means of private investors, WeWork turned to the public markets. Initial plans were to raise as much as $4bn, with additional debt financing that was contingent on a successful IPO. However, the firm’s investment bankers outright failed to find interest in the offering at valuations south of $20bn (a more than 50% discount to its valuation less than a year ago in the SoftBank raise). This put pressure on Founder and CEO Adam Neumann and shed light on some of his questionable management tactics, financial decisions, and general ability to lead the potentially publicly traded company into the future. He was eventually forced out and the once talked about IPO plans were scrapped until further notice.

On October 22nd, news broke that SoftBank was looking to take control of WeWork for a valuation of $8bn. This a massive 83% decline from the $47bn valuation from SoftBank in January 2019. To add salt to the wound, WeWork has announced the need to let go of up to 2,000 of its employees, but reports indicate a lack of liquidity to finance severance packages. Despite that fact, the latest details of SoftBank’s rescue package will net Adam Neumann north of $1.5bn. This on top of the $700m the former CEO yielded through share sales and loans in early 2019.

Observers have been meticulously dissecting what exactly went wrong in the WeWork saga. And there is certainly no shortage of material to chew on. There are also a ton of things that went right. Things that, to a certain degree, have entrenched the markets ability to self-regulate the common excesses of too many unicorns and newly minted “decahorns.” Perhaps the most reassuring result of this whole ordeal is that the risk and losses associated with WeWork and its future will remain privatized. There will be no private profits and public losses. SoftBank, who on its own accord inflated the valuation balloon, will feel the full financial effect of those decisions. There is undoubtedly collateral damage in the form of employee. And worst of all, it seems Adam Neumann, who was the cause of much of the problem, will walk away a billionaire with only a badly damaged ego.

The hope is that the public market reaction to the WeWork story will provide a cautious tale to other startups who hope to follow in its footsteps. Growth, and in particular increasingly unprofitable growth, is not a cure all for poor business decisions. Changing your slogan to include platitudes and feel goods like “Elevating the World’s Consciousness” will not pull the wool over investor’s eyes as to the faults of your business model. And last but not least, hopefully this will dissuade private investors from subsidizing inherently unprofitable companies to carve out markets that they cannot sustain over the long-term. We’ll see if the same lesson rings true the next time a “technology” business tries to disrupt and innovate on a grand scale.